Understanding Your Truth App - A Personal Connection

Have you ever stopped to think about what "truth" really means to you? It's something we talk about a lot, but its personal side often gets overlooked. We might say something like "chocolate tastes good," and for us, that's absolutely true. Yet, it isn't a universally accepted fact, is it? This idea, that what feels right to one person might be different for another, shapes so much of how we experience the world around us.

Consider, if you will, the feelings we hold deep inside. Saying "I love my mom," for instance, expresses a profound personal conviction. This sentiment, you know, holds a powerful truth for the person who feels it, even if it cannot be measured or proven in a scientific way. It’s a feeling that exists as a personal truth, quite separate from something that could be written down as a hard piece of information. This distinction between what is simply true for us and what is a cold, hard piece of information is something worth thinking about.

And what about bigger ideas, like the existence of a higher power? For many, this is a deeply held conviction, a truth that guides their life. But, just like the taste of chocolate or a mother's affection, it doesn't quite fit into the box of something you can verify with a measuring stick. This makes us wonder, doesn't it, how an app, a piece of software, could possibly begin to make sense of these very personal, very human ways of seeing what is real.

Table of Contents

- What Makes Something True for You?

- Is Truth Just a Fact-Finding Mission?

- How Does Our View of Truth Change?

- What Could a Truth App Actually Do?

What Makes Something True for You?

It's interesting, really, to think about how we decide what counts as something that is true. For many of us, what we consider true is very much tied to our own experiences and feelings. When we say, "chocolate is good," that’s a statement of personal preference, a feeling that holds a certain validity for the person speaking it. It’s not something you can argue with, because it comes from inside. This kind of personal conviction is a very different sort of truth from, say, the statement that the sky is blue, which most people can agree on based on what they see.

This idea extends to our deepest connections, too. When someone says, "I love my mom," that’s a powerful declaration of affection. It’s a heartfelt belief, a deep-seated feeling that, in a way, becomes a truth for that individual. You can't really prove or disprove it with evidence; it just exists as a part of their emotional landscape. This sort of personal truth, you know, is something we often take for granted, but it shapes so much of our daily interactions and how we see the world.

Then there are those bigger, more abstract concepts, like whether a higher being exists. For many, this is a deeply held conviction, a guiding light that shapes their entire outlook on life. It's a truth that provides comfort and meaning, yet it's not something that can be verified through typical means. It exists as a belief, a personal reality, and that, in itself, is a kind of truth for those who hold it. So, you see, what we accept as true can come in many different forms, some quite solid, others much more personal and fluid.

Personal Views and the Truth App

Given how varied our personal convictions can be, a "truth app" might help us explore these individual ways of seeing things. It could, perhaps, offer a space where people can record their own personal convictions, like "chocolate is good," and see how those compare to what others feel. This would be a way to show that truth isn't always about universal agreement, but often about what resonates with an individual. It’s about creating a place where those subjective experiences are acknowledged and given a certain weight.

Such an app might also provide a way for us to reflect on why we hold certain convictions. For example, why do I feel that "I love my mom" is a truth? Is it because of shared memories, or just an innate bond? The "truth app" could prompt users to consider the foundations of their personal convictions, leading to a deeper appreciation of their own inner workings. It could be a tool for self-discovery, really, helping us to sort through the many different things we hold to be true.

Moreover, when it comes to more abstract convictions, like the existence of a higher power, a "truth app" could offer a forum for respectful sharing. It wouldn't try to prove or disprove these convictions, but rather, provide a platform for people to express what is true for them, and perhaps see how many others share similar personal realities. This approach respects the personal nature of such convictions, making it clear that truth, in this context, is about individual belief rather than universal proof. It’s about creating a sense of shared human experience, even when the underlying convictions are deeply personal.

Is Truth Just a Fact-Finding Mission?

Many people tend to think of truth as something that is simply a piece of information, something that can be proven or disproven with evidence. Like, the statement "the Earth is round" is a piece of information that we can verify. But, as we've talked about, a lot of what we consider true doesn't fit into that neat little box. Things like "chocolate is good" or "I love my mom" are true for the person experiencing them, but they aren't pieces of information that can be universally confirmed. They are more about feeling and personal experience than about objective measurement.

This distinction is important because it changes how we approach discussions about what is real. If we always expect truth to be a hard piece of information, we might miss out on the richness of human experience and the validity of personal feelings. The idea that something can be true without being a cold, hard piece of information is something that some thinkers have explored quite a bit. They suggest that what we call truth is less about a fixed reality and more about how we use language to talk about what we believe.

This way of thinking, sometimes called "deflationism," suggests that when we say something is "true," we're not really describing a special quality of that thing. Instead, we're simply agreeing with it, or endorsing it. So, saying "it is true that chocolate is good" is just another way of saying "chocolate is good." It's not adding any new information about chocolate; it's just expressing our agreement. This idea, you know, makes us reconsider what we mean when we talk about things being true.

Beyond Simple Facts - The Truth App Perspective

If we accept that truth isn't always a simple piece of information, then a "truth app" would need to go beyond just checking facts. It wouldn't be like a search engine that gives you verified data. Instead, it might be a tool for collecting and organizing what people consider to be true, even if those convictions are deeply personal. This could mean categorizing beliefs as "personal convictions" versus "shared observations," allowing users to see the different ways in which something can be considered valid.

Such an app could also help people explore the concept of truth as a collection of judgments. The idea here is that what we call "truth" and "falsehood" are really just groups of things we decide are consistent or inconsistent. For instance, if you judge that "chocolate is good," and you also judge that "things that are good make me happy," then it would be consistent to judge that "chocolate makes me happy." A "truth app" might help users map out these connections between their different judgments, showing how their personal convictions hang together.

Furthermore, the "truth app" could allow users to see how what they consider true depends on their own viewpoint. The provided text mentions that "truth depends on the person establishing a truth." This means that what is true for one person might not be true for another, simply because they are looking at things from a different angle. The app could, for example, present a statement and then allow different users to mark it as "true for me" or "not true for me," creating a visual representation of how personal perspectives shape what we believe to be real.

How Does Our View of Truth Change?

It’s quite fascinating, really, how what we consider true can shift and change, sometimes even depending on our very existence. The idea that certain universal principles, like the rules of nature or even basic logic, might only be true as long as we, as thinking beings, are around to perceive them, is a rather deep thought. It suggests that our presence, our way of seeing and interpreting the world, plays a part in making things true. This means that truth isn't just out there, waiting to be discovered, but is, in a way, connected to our human experience.

Think about it this way: what if the way we understand the world, our very framework for making sense of things, is what gives certain statements their "truth"? If we weren't here to observe and make sense of things, would Newton's laws still hold true in the same way? This isn't to say that the apple wouldn't fall from the tree, but rather that the *truth* of Newton's laws, as a piece of knowledge, is tied to our ability to formulate and grasp them. So, in some respects, truth is a very human construct.

And then there's the idea of relative truth versus absolute truth. The provided text suggests that all relative truths are just different ways of getting close to one big, unchanging truth. So, your personal conviction that "chocolate is good" is a relative truth, a small piece of a larger, perhaps unknowable, absolute truth about what is good in the world. This way of thinking suggests that our individual experiences and beliefs are like different paths leading towards a single, ultimate reality, even if we can only ever get approximations of it.

The Truth App and Shifting Beliefs

Considering how truth can be so personal and even tied to our perspective, a "truth app" could become a tool for exploring how our convictions evolve. It might allow users to track their own beliefs over time, seeing if what they considered true a year ago still holds up today. This kind of personal history of convictions could be quite revealing, showing how life experiences and new information can reshape our inner sense of what is real. It’s almost like a journal for your deepest convictions.

The "truth app" could also help us understand the moral side of truth-telling. The text mentions that if we always had to tell the absolute truth, without any consideration for consequences, society would probably fall apart. This suggests that the practical application of truth-telling is complex. An app might present scenarios where users have to weigh the importance of absolute honesty against other values, like kindness or social harmony, helping them to think through the real-world implications of their personal convictions about truthfulness. It could be a space for ethical reflection, really.

Furthermore, the app could help users understand the idea of "truth value," which is simply how a piece of knowledge relates to reality. A statement that doesn't describe reality accurately would have a "false truth value." The "truth app" could offer exercises where users evaluate statements and consider whether they align with their understanding of reality, helping them to sharpen their ability to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate descriptions of the world. It’s about building a sense of discernment, you know, helping people to make better judgments about what they encounter.

What Could a Truth App Actually Do?

Given all these different ways of looking at what is true, what might a "truth app" actually offer? It wouldn't be about giving you definitive answers, because as we've seen, truth is often quite personal and dependent on perspective. Instead, it could be a space for personal exploration, a place where you can consider your own convictions and how they fit into the broader picture of what people believe. It might, for instance, let you record your own personal truths and then see how logically consistent they are with other things you believe. This would be a way to check your own internal reasoning.

The app could also help users think about the qualities of truth itself. The provided text suggests that truth must be the origin or the driving force behind something, rather than just an outcome. It must, in a way, be fundamental. A "truth app" might prompt users to consider whether their own deeply held convictions feel like origins or effects. For example, does your belief in something feel like it comes from a deep, foundational place, or is it a result of something else? This kind of reflection can help clarify the nature of one's own beliefs.

Finally, a "truth app" could provide a platform for people to discuss the finer points of what it means for something to be true. The text mentions that "accuracy" is often thought of as the same as truth, but questions whether this is entirely correct. An app could facilitate conversations where users share their thoughts on these subtle distinctions, helping everyone involved to refine their own ideas about what makes something genuinely true. It’s about creating a community of thoughtful individuals, really, all trying to make sense of this very human concept.

So, we've taken a little look at how complex and personal the idea of truth can be, from our favorite foods to our deepest beliefs. We've explored how truth isn't always a simple piece of information, but often a collection of judgments that depend on who's doing the observing. We've also touched on the idea that our views of what's true can shift and change, and how even the moral side of telling the truth isn't always straightforward. And through it all, we've thought about how a "truth app" might help us explore these very human ways of understanding what is real, offering a space for personal reflection and shared discussion about our many different convictions.

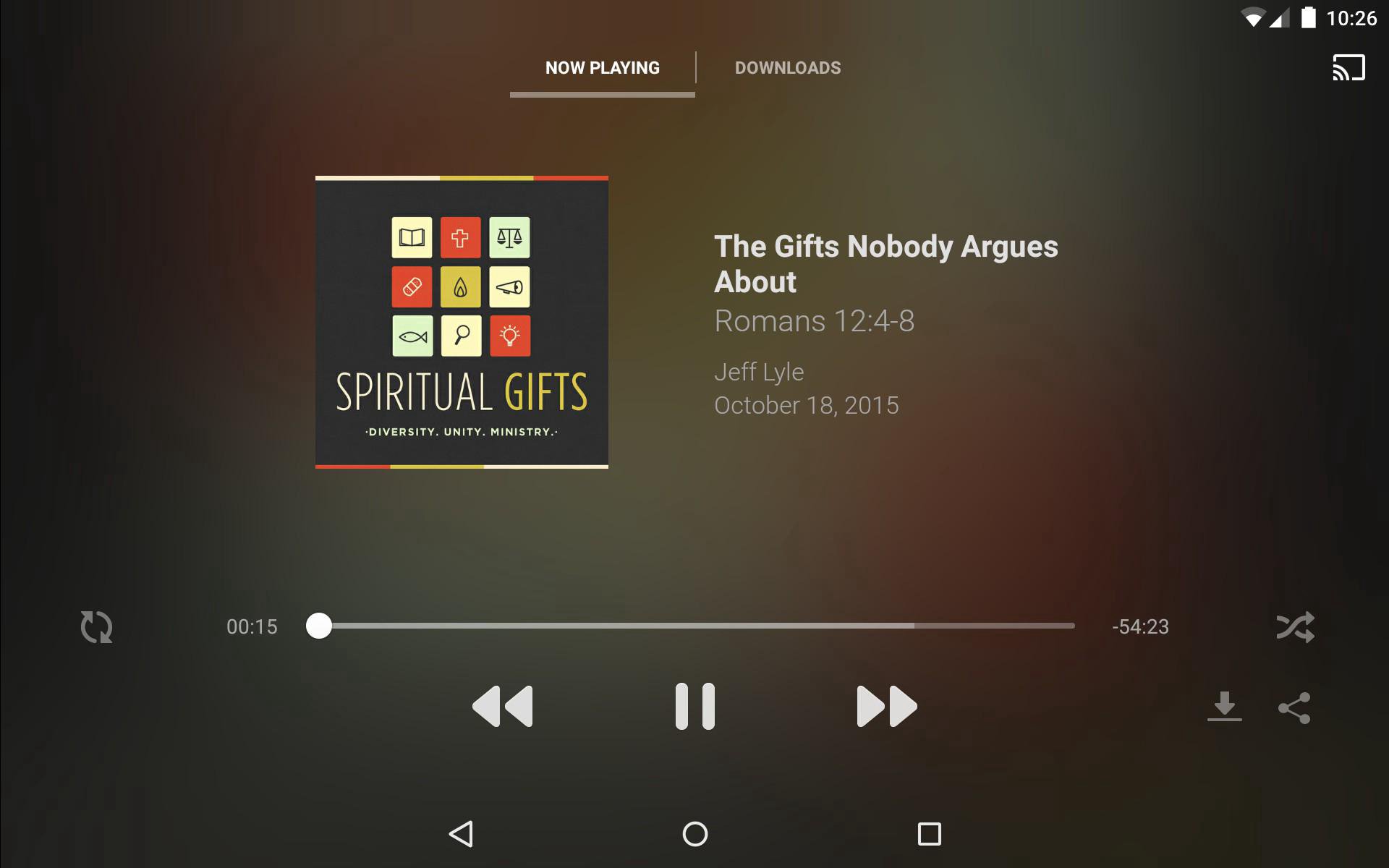

App - Transforming Truth App

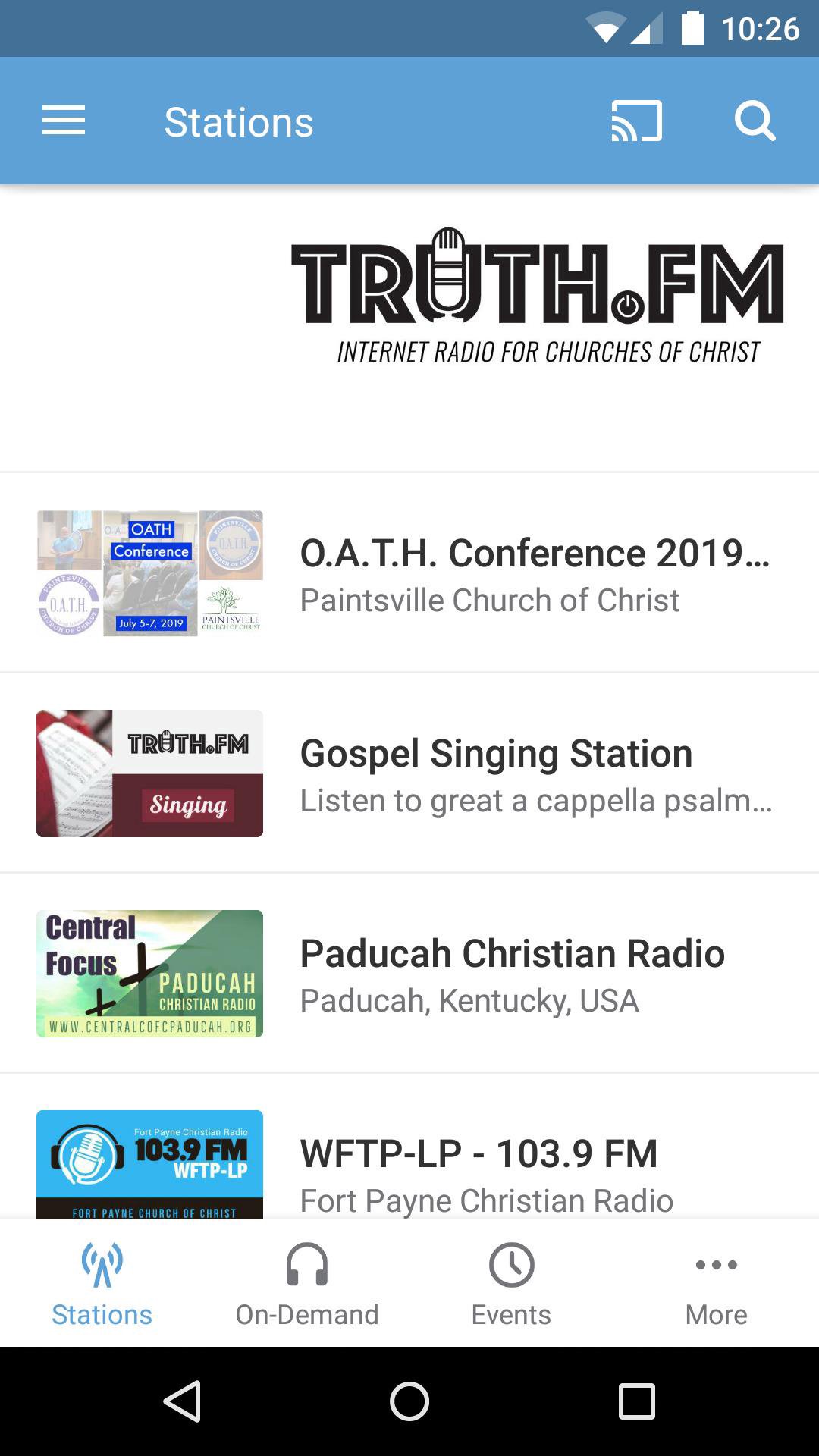

App - Truth.FM

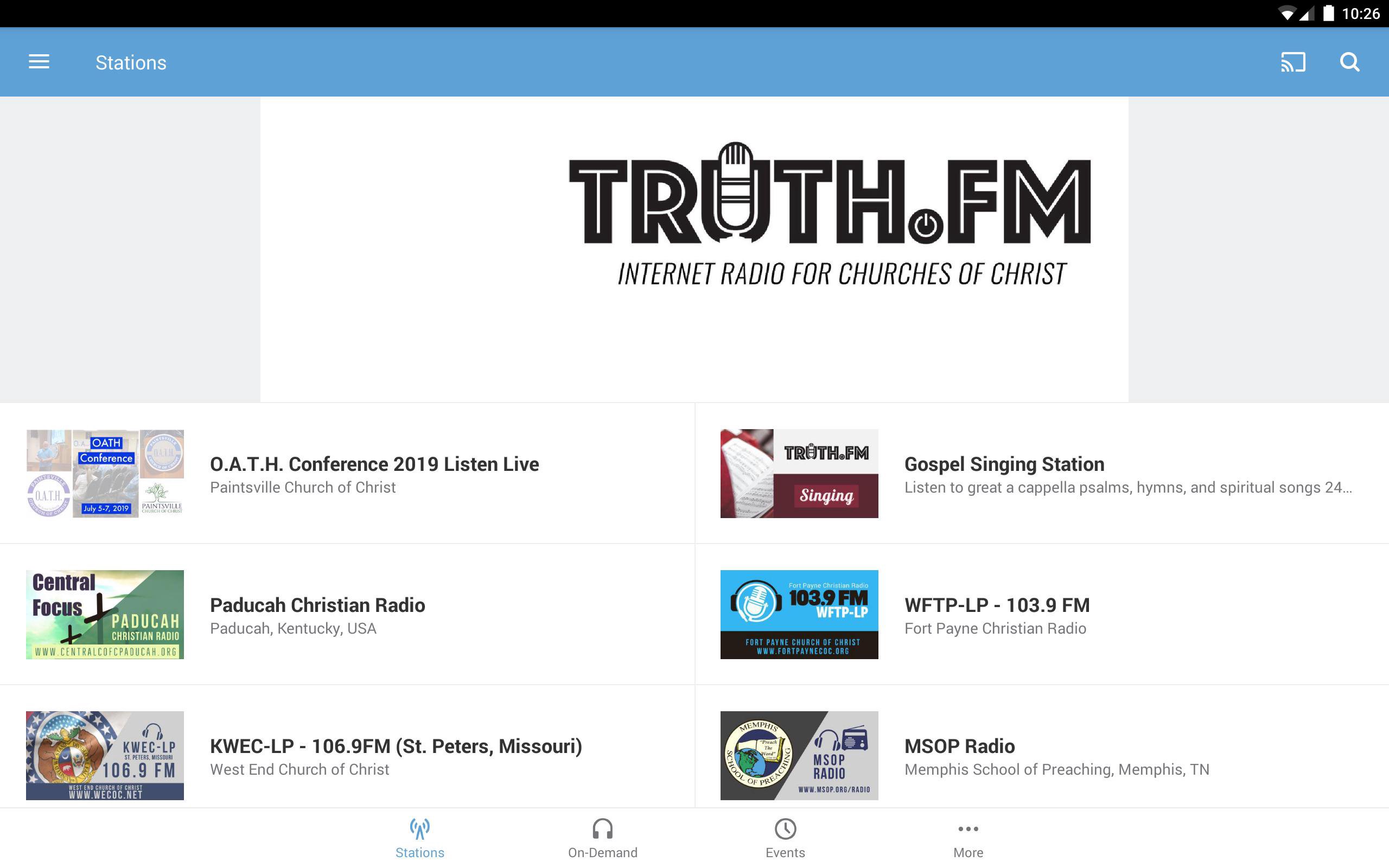

App - Truth.FM